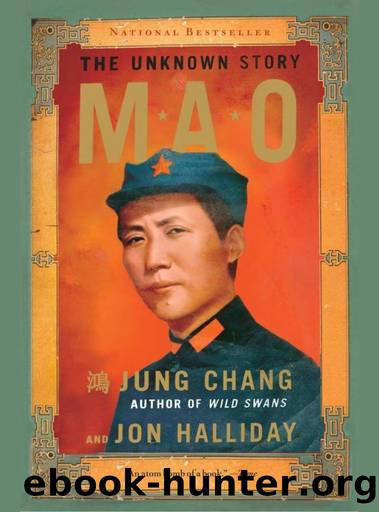

Mao: The Unknown Story by Jung Chang & Jon Halliday

Author:Jung Chang & Jon Halliday [Chang, Jung]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Tags: Communism, China, Politics, War, Biography, History

ISBN: 9780307807137

Publisher: Anchor

Published: 2002-08-31T23:00:00+00:00

38

UNDERMINING KHRUSHCHEV

(1956â59 AGE 62â65)

WITHIN MONTHS of denouncing Stalin, Khrushchev had run into trouble. In June 1956, protests erupted in Poland at a factory suitably named âthe Stalin Worksâ in the city of Poznan, and more than fifty workers were killed. Wladyslaw Gomulka, a former Party leader who had been imprisoned under Stalin, returned to power, espousing a more independent relationship with Moscow. On 19 October the Russians told Mao that anti-Soviet feelings were running high in Poland, and that they were thinking of using force to keep control.

Mao saw this as an ideal opening to undermine Khrushchev by presenting himself as the champion of the Poles and the opponent of âSoviet military intervention.â As this might involve a clash with Khrushchev, Mao weighed the pros and cons long and carefully, lying in bed. He convened the Politburo on the afternoon of the 20th. None counseled caution. Then, clad in a toweling robe, he summoned Russian ambassador Yudin and told him: If the Soviet army uses force in Poland, we will condemn you publicly. He asked Yudin to phone Khrushchev straight away. By now, Mao had concluded that Khrushchev was something of a âblunderer,â who was âdisaster-prone.â The awe he had felt for Khrushchev at the time when the Soviet leader denounced Stalin was rapidly fading, replaced by a confidence that he could turn Khrushchevâs vulnerability to his own advantage.

Before Yudinâs message reached the Kremlin, Khrushchev had already made the decision not to use troops. On the 21st he invited the CCP and four other ruling parties to Moscow to discuss the crisis. Mao sent Liu Shao-chi, with instructions to criticize Russia for its âgreat-power chauvinismâ and for envisaging âmilitary intervention.â In Moscow, Liu proposed that the Soviet leadership make âself-criticisms.â Mao was aiming to cut Khrushchev down to size as leader of the Communist bloc, and make his own bid for the leadership, which had been his dream since Stalinâs death. Now an opportunity had come.

At this juncture, another satellite, Hungary, exploded. The Hungarian Uprising was to be the biggest crisis to date for the Communist worldâan attempt not just to gain more independence from Moscow (which was the aim in Poland), but to overthrow the Communist regime and break away completely from the bloc. On 29 October the Russians decided to withdraw their troops from Hungary, and informed Peking. Up till this point, Mao had been urging a pull-back of Soviet forces from Eastern Europe, but he now realized that the regime in Hungary would collapse if the Russians left. So the next day he strongly recommended that the Soviet army stay on in Hungary and crush the uprising. Keeping Eastern Europe under communism took priority over weakening Khrushchev. Maoâs bid to become the head of the Communist camp would be worthless if the camp ceased to exist.

On 1 November, Moscow reversed itself. Its army remained in Hungary, and put down the Uprising with much bloodshed. The realisation that Russian troops were essential to keep the European satellites under Communist rule was a blow to Maoâs designs to ease these countries out of Moscowâs clutches.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4280)

Never by Ken Follett(3917)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3834)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3361)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3349)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3054)

Will by Will Smith(2890)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2339)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2316)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2309)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2289)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2210)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2208)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2177)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2177)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2103)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2079)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2043)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1996)